On Maya Deren

“I was a poet before I was a filmmaker. And I was a very poor poet because I thought in terms of images, what existed essentially as a visual experience in my mind. Poetry was an effort to put it into verbal terms. When I got a camera in my hand it was like coming home. It was doing what I always wanted to do without the need to translate it into a verbal form”

–Maya Deren

Stan Brakhage once said that Maya Deren was “the mother of us all.” What he meant by this was that Maya was a significant influence to all experimental films and filmmakers that came after her. The purpose of this paper is to find out exactly what Brakhage meant; just how big of an impact did Deren have on the experimental film scene? The first part of this paper will be a biography and analysis of Deren and her work. The second part will compare and contrast Deren’s aesthetics to experimental films that came after her in hopes of finding out exactly what Brakhage meant.

Maya Deren was actually born Elenora Derenkowsky.[1] She was born in Kiev, Ukraine, on April 24th, 1917. Her parents were both educated: her mother was a musician and her father was a psychiatrist. They moved to New York in 1922 due to the rise of anti-Semitism in Europe during this time. Her family took the last name “Deren,” which was the Americanization of Derenkowsky.

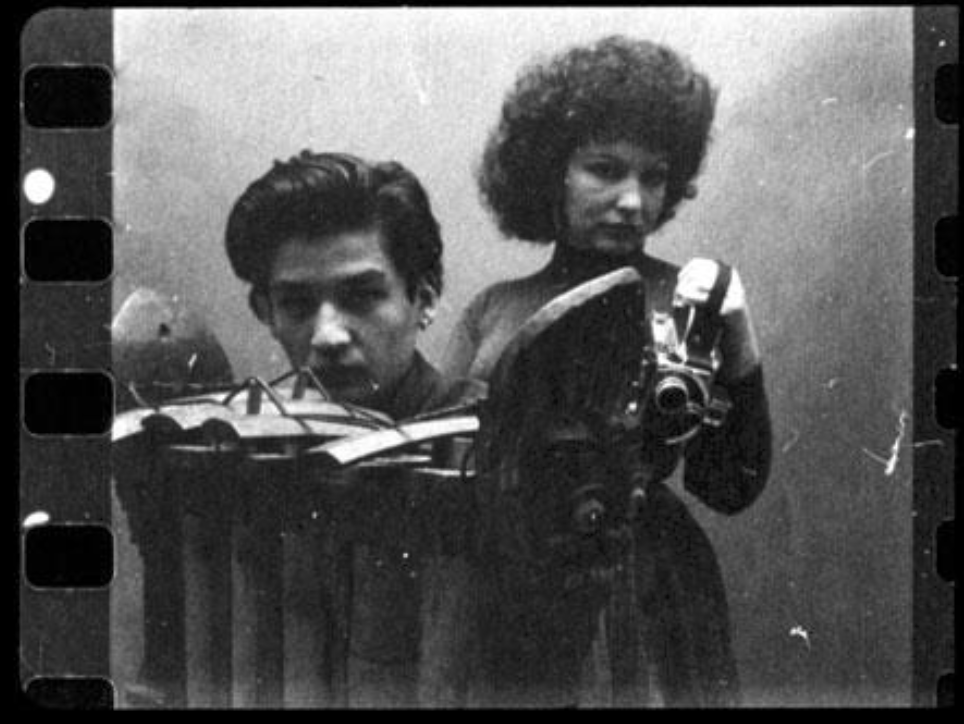

Elenora had a hard time adjusting to a new language and culture, as would anyone at age five. When she grew up, she studied journalism and political science at Syracuse University. Deren become interested in filmmaking, dancing, poetry, and Socialism. After marrying Gregory Bardacke, she received her BA from New York University and went on to graduate from Smith College with a master’s degree in English. Upon graduation Deren began working as a secretary for Katherine Dunham, who was an anthropologist as well as a choreographer. Gregory and her were divorced in 1939. While working on a production for Dunham’s company Deren met a Czech filmmaker, Alexander Hammid. They married and according to Hammid, it was he who suggested that she changed her name to Maya; Maya was the name of the Mayan goddess of water. In 1943 Deren and Hammid began working on a film that would launch Maya’s filmmaking career.

Meshes of the Afternoon beings with an arm dropping a single flower on the ground. A woman follows a hooded figure with a mirror-face. She drops a key, which later turns into a knife. She goes to her bedroom and watches herself follow the figure and enter the house. She interacts with several other versions of herself and she even tries to kill one. Reflections. Mirrors shatter. The ocean.

In 1943 Deren worked on a film entitled Witch’s Cradle with Marcel Duchamp. Duchamp was a French artist and filmmaker who had a heavy influence in Dada and surrealist films; his significant contribution to film was Anemic Cinema. The film went unfinished and Maya started working on At Land. At Land starts with waves, which wash a woman onto the shore. The waves then go back to the ocean, reversing. The woman climbs and enters a boardroom where she watches a game of chess happen by itself. She steals a chess piece, loses it, and spends the rest of the film trying to find it, encountering cliffs and a couple on the beach. Several versions of her exist on the beach and one of them steals the chess piece from the couple and runs away while the other versions watch her.

In her first two films, Meshes of the Afternoon and At Land, Deren was working in a hybrid of psychodrama and surrealism. When a filmmaker makes a psychodramatic film he or she is using the art form to try to express what is going on inside their mind. It is an exercise is turning thoughts and emotions into something visible. The use of mirrors and several different versions of Maya in Meshes of the Afternoon could be speaking to lack of self-realization or confirmation of reality. A similar idea is seen in At Land. The main character searches for, steals, and then loses a chess piece and then spends the rest of the film trying to find it again. What the chess piece represents is open to interpretation, but notice with what intensity she goes about trying to find it: she goes unnoticed in a boardroom full of higher-ups, crawling. At one point another version of her steals it from the couple playing chess on the beach and all versions of her watch her run away. This, again, could speak to the search for true self or true reality.

Surrealism in film speaks to dreamlike images, especially juxtaposing dissimilar images together. The most obvious surrealist element in Meshes in the Afternoon would be the anachronisms of Maya watching herself walk around the bend and the different versions of herself interacting with each other. In At Land, notice the position of the beach, boardroom and jungle. This is also surrealistic as it follows dream logic, where the dreamer can turn around or close their eyes and be in a completely different environment than they were before. While the surrealistic elements in Deren’s work seem to be obvious, she did not see herself as a surrealist at all. In fact, she attacks surrealism because she felt that it lacks the ability to show human consciousness. Despite the temporal anomalies and juxtapositions Maya felt her imagery itself was not surrealist, but direct. For example, with the four strides in Meshes of the Afternoon when she walks to herself with knife in hand and you see her foot in different landscapes, Maya was saying that “…you have come a long way-from the beginning of time-to kill yourself.” While some of the elements in her films were surreal, she intended her images to have a definite interpretation and direct meaning.

Maya had been screening her work and lecturing at different universities. In 1945 she made another film with her husband, The Private Life of a Cat. The Private Life of a Cat is a thirty-minute short film that shows the mating ritual and birth of cats. Hammid directed and the film is attributed to him. The next film Maya did was A Study in Choreography For Camera, starring Tally Beatty. Tally dances in front of different locations. What is so interesting about A Study in Choreography is the use of framing. Deren uses space to express ideas and feelings. In one particular scene Tally spins in front of a statue with several different faces. At different points during the dance it appears that his face is part of the statue. In A Study in Choreography for Camera Deren takes a completely different approach to her work. Instead of relying on her inside thoughts and emotions to tell a story she is more interested in outside space and movement. There is still a tinge of surrealism with the changing of environments, but this film is more interested in the dancer and the framing of the images that the camera creates. There is a focus on form over content.

In 1946 Maya completed A Ritual in Transfigured Time. A Ritual in Transfigured Time blends the psychodramatic and surrealistic elements of her first two films while incorporating the interest in dance and movement from A Study in Choreography for Camera. In true psychodramatic fashion, the main character is played by two different people: Maya Deren and Rita Christiani. The majority of the film takes place in and around what appears to be a funeral, though people are dancing. Rita/Maya seem to be searching for something or someone (self-actualization). Several men show interest in dancing with her, though she is not interested. She finds someone she is interested with and they kiss and then are transported outside. They dance, but then realizing what the man represents, she runs away. She runs frantically while he follows her, dancing gracefully; she is moving faster, but cannot seem to get away from the man. She runs into the sea and we see an inverted image and her in a wedding dress, floating in the water. In The Mirror of Maya Deren, Rita Christiani reveals what Ritual in Transfigured Time was about. With tears in her eyes she explains that it was about the conflict between the hope for some kind of life or consciousness after death and the reality that there is none.[2]

This year she also received the Guggenheim Fellowship for Creative Work in the Field of Motion Pictures. This was the first time a filmmaker had won the Guggenheim. The following year Meshes of the Afternoon won first prize at Cannes in the experimental film category. This was also the year that she and Hammid divorced. Brakhage was a personal friend of Maya and claims that the breakup had to do with the fact that Hammid had always felt Maya overshadowed him; he felt as though he never received credit for his contributions to her works.

She used the money from the Guggenheim grant to travel to Haiti. She had been interested in their culture, especially the Voudoun (Voodoo) dancing rituals. Maya believed that those practicing Voudoun actually went into a religious trance from their ritualistic dancing. In 1948 she released Meditation on Violence. The first half of Meditation on Violence features Chao-Li Chi performing different tai chi moves. At one point in the film he jumps and is transported to a different place and now carries a sword. The film then goes in reverse to the beginning. The film expresses how beauty could turn to violence in just a jump. With A Meditation on Violence, Deren essentially takes the approach used in A Study of Choreography for Camera and adds some meaning to it. Instead of using the body movements purely as form, she uses the body movements of tai chi to send a message. She examines the line between beauty and violence, almost blurring it.

Maya made several trips to Haiti from New York in the following years. She became very involved in the Voudoun culture. That culture eventually accepted her and even initiated her as a Voudoun priestess. Her focus had shifted from film to Voudoun. During this time she had started three different films: Medusa, Haiku, and Ensemble for Somnambulists. None of these films were ever completed. Aside from the concentration on Haiti, Maya also fell in love with a Japanese musician, Teiji Ito. When they met Maya was forty-three, eighteen years Ito’s senior.. He lived with her and went with her on her trips to Haiti. In 1953 she published Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti. Which was a book about her experience in Haiti, especially her religious experiences regarding Voudoun. She had shot almost 20,000 feet of film during her trips to Haiti. It was too much for her to edit and she never got around to editing it.

The Very Eye of Night was her last film. She had finished it in 1955, but it was not released until 1959. Ito did the soundtrack as well as composing new music for Meshes in the Afternoon. The overall opinion of The Very Eye of Night was that Deren had lost her touch. She was most known for her early psychodramas and this film was certainly a departure. Inverted images of dancers were seen in front of an intentionally fake starry space scene. It did not quite work as a visual study and as a psychodramatic or surrealist film it did not give the audience much to dissect or interpret. Stan Brakhage explains that when the film was released only about four people knew what the film was about; it had a secret meaning. That meaning has something to do with Maya’s Voudoun belief that humans are the shadow of God and that each person decides to be shadow or light.

Mays married Ito in 1960, but the marriage did not last long as she died on October 13, 1961 from a brain hemorrhage. She had been taking sleeping pills as well as “vitamin shots” prescribed by Dr. Max Jacobson. Jacobson is now infamous for prescribing high amount of amphetamines to his high-profile patients. Her ashes were taken and scattered around Mount Fuji. Ito offered her Haiti film to any interested filmmakers, but there were no takers so in 1985 Ito and his second-wife, Cherel, released it themselves. The film was titled Divine Horsemen. Ito did the music.

Coming back to Brakhage’s quote, what of Maya’s influence can seen in the history of experimental cinema? The rest of this paper will compare and contrast Maya’s work to the more widely known experimental films and movements that came after her. The 1950s saw the rise of the psychodrama, starting with Kenneth Anger’s Fireworks in 1949. Maya’s influence here can be seen throughout. This film has several similarities between Maya’s early surrealist psychodramas. The most obvious is the anachronistic environments; notice the door that leads to an impossible place. Maya’s early films focused on self-realization or identity. Anger’s film is also about identity, though here it is about sexual identity. The most noticeable difference here is violence. Violence in Deren’s films was usually implied or suggested by a metaphor, making her work quiet and beautiful. To Anger, violence was aggressive and direct.

In he 1960s several filmmakers wanted to return to a simpler kind of filmmaking. P. Adams Sitney referred to the films made in this movement as structural. There were four characteristics inherit to structural Film. The first is that the camera is fixed. The second is the use of a strobe or flicker effect. The third is looping or some kind of repetition. Photo retouching in postproduction is the last characteristic. The films also tended to value form over content.

Deren’s films have very little in common with the structural movement. The camera is almost never static in her work. In fact, how the camera interacts with the environment is essential to her body of work. One could argue that the dance sequences in The Very Eye of Night count as repetition or looping. The reversing of Chao-Li Chi’s martial arts performance in Meditation on Violence is a kind of reverse loop or repetition. There was also no photo retouching as far I one can tell. What Maya’s work had most in common with the structuralists would be her emphasis on form over content. Of course, you could also say some of the structuralists owe something to her for the obsession of movement or emphasis on gesture as form, just look at structural films like Colorfilm and Nostalgia. It is not surprising they have so little in common with Maya’s work; structural films were made to be simple. They were a response to complicated experimental films, ones like Maya made.

Stan Brakhage was a friend and somewhat of a protégé to Deren. He even lived with Maya at one point. It is no surprise that his films share several similarities with Deren’s work. Like Meditation on Violence, Brakhage’s Dog Star Man: Part One focuses on movement or gesture in order to tell a story. That is, the form of the film is movement in itself. Kenneth Anger’s Eaux d’Artifice and Charles Boultenhouse’s Handwritten would be other examples. Sitney refers to these films as imagist films.[3]

Brakhage’s films often used the physical painting or scratching of the film itself. Take, for example, The Dante Quartet. Though not based on a simple gesture, one could argue it to be an imagist film: the paint just takes the place of the dancer and the gesture made. It would be interesting to see what Deren thought of Brakhage’s painted films as she dismissed graphic films on the basis that they reject the reality of the photographic image.

She also rejected documentaries because she felt they excluded imagination. Not surprisingly, her body of work and the autobiographical experimental films share very little in common. In autobiographical films a story is told from first-person. If Deren made such a film it would attempt to show the mental landscape of the person, not retell or reshow the incident.

In the contemporary experimental film scene Maya’s influence can seen plainly. Barbara Hammer openly talks about using Maya as an influence for her work.[4] Hammer saw Meshes of the Afternoon in her film history class and said she was the only woman director the professor screened all class; Meshes gave her reason to believe she could be a filmmaker. Hammer is especially interested in Maya’s concept of vertical filmmaking. Vertical filmmaking means that many different emotions are pulled from the audience at once while looking at a film image or a juxtaposition of images. Hammer achieves this by laying images whereas Deren was able to achieve it by showing a singular image. This can be seen in Hammer’s short film A Horse is Not a Metaphor.

The films of David Lynch closely resemble Deren’s combination of psychodramatic and surrealist elements. The ending scene of Mulholland Drive when Betty/Diane’s feelings of guilt manifest themselves as her grandparents crawling under the door is similar to Deren’s early psychodramas. Lynch uses the idea of “a woman in trouble” in Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire. Both of these films also feature women with more than one self who are searching for their identity. The connection to Deren should be obvious. The causality loop or spiraling narrative used in Lost Highway is similar to the one used in Meshes.

The paper thus far has commented only on the aesthetic influence Maya has had on other experimental filmmakers. It should be noted that her life itself shares several similarities with experimental filmmakers. First off, she did not have a lot of money. A lot of her work was actually shot in her home. She was thrilled when she actually got to shoot The Very Eye of Night in an actual studio. Before she died it was said that she was not eating much, spending what money her and Ito had on their cats. There is also the use of drugs, especially amphetamines. Lastly, there seems to be a trend among experimental filmmakers to take up non-Christian religions that focus on meditation, or becoming interested in meditation itself. Of course, these characteristics could be true for anyone, but in doing research on Maya the author found these similarities between her and several other experimental filmmakers and felt they should be noted. This is not pointed out to generalize or belittle, but to explore the idea that Maya’s impact on experimental film might not stop at aesthetic technique, perhaps she defined a lifestyle.

So, what did Brakhage mean with his quote? Whether future filmmakers borrowed, built upon, reacted to, or outwardly stole from Maya’s work, her influence is undeniable. She gave birth to new ways to approach film, or art in general. Through her work she embodies a force that is to be loved or hated and everything in between. She paved the way for other experimental filmmakers. Her work demands a reaction, just like any good mother.

________

[1] Haslem, Wendy. “Maya Deren.” Issue 51, 2009 – Senses of Cinema.. 22 Nov 2010.

[2] The Mirror of Maya Deren. Dir. Martina Kudlácek. Zeitgeist Video, 2002. Film.

[3] Sitney, P A. Visionary Film: The American Avant-Garde, 1943-2000. Page 22. Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 2002. Print.

[4] MoMa. (2009, August 4). Modern Women: Barbara Hammer on Maya Deren.

<http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3pTVbQilDqY>. Video File.

[…] written previously about Maya Deren’s work, so I won’t go into detail here. Meshes is her most well-known film and for good reason, it’s […]