-

What Can’t You Put On A Billboard?

Since my time working in the out-of-home industry was recently put to an end, I thought I’d answer one of the most common questions I’d get: what can’t you put on a billboard? The answer is almost as nebulous as the question itself. Let’s take a look at a billboard that was recently taken down.

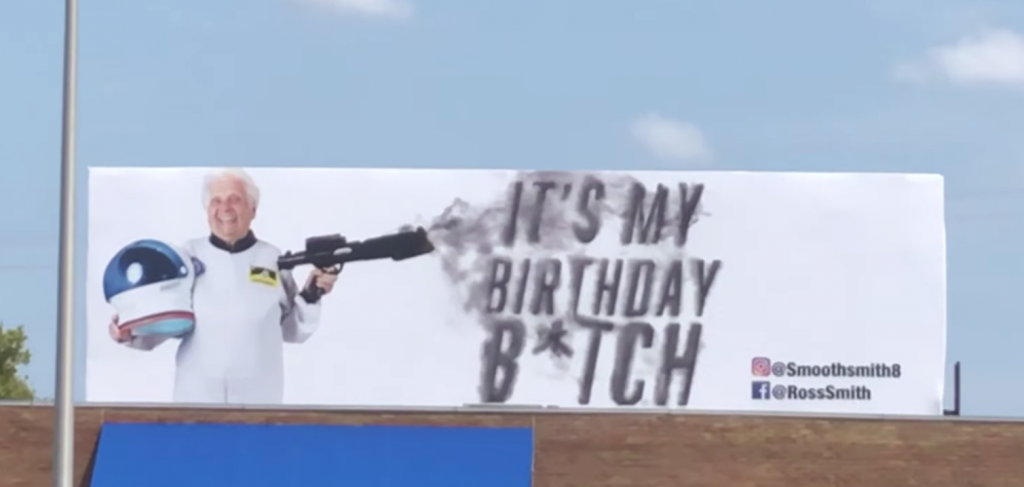

This controversial billboard (pictured above) was recently taken down in Columbus, Ohio. It features an elderly woman in a spacesuit, holding a helmet in one hand and a gun in the other. The text on the billboards reads, “It’s my birthday, b*tch.”

It was purchased by social media and viral video star, Ross Smith. The woman on the billboard is Ross’s grandmother, who frequently appears in his videos. According to Ross, the billboard was supposed to be a birthday present for his grandma and its intent was to mock the “Storm Area 51” movement.

After the mass shootings in El Paso on Aug. 3rd and Dayton on Aug. 4th, the billboard company received several complaints about the billboard. It was removed immediately.

There are a lot of opinions about removing this billboard, both for and against. Many people can’t believe it ever went up in the first place. What actually is and isn’t allowed on a billboard, anyhow? Previously, buying a billboard meant you bought from an advertising expert, so knowing content regulations wasn’t necessary. Technology now allows anyone to buy a billboard online, so it’s more important for media buyers and marketers to understand the rules and regulations.

-

From Astral Chain To Zetman: The Story Of Masakazu Katsura

Although he’s a famous manga artist in Japan, there’s a good chance you’ve probably never heard of Masakazu Katsura – and if you have, it probably wasn’t until very recently. He’s the character designer for Astral Chain, the latest action title from PlatinumGames. In anticipation of Astral Chain’s release, we’re taking a tour through some of his previous work so you can become better acquainted with his output (if you’re not one of the lucky people who’s already a fan, of course).

Masakazu Katsura was born in Japan in 1962. Growing up, he was always good at drawing, though amazingly, he never wanted to be a manga artist and had little interest in the medium, preferring movies and novels. He entered a manga contest when he was in high school purely so he could raise the funds to buy a stereo with the prize money; fame was not at the forefront of his mind at that time. As it turned out, he ended up winning the award and it launched his career.

Grab a box of tissues and get ready to nurse those broken hearts as we take a look back at some of Katsura’s career-defining titles.

This article was written for Nintendo Life. Please read the full article here.

-

Christina Kubisch and Her Electrical Walks

I wrote this paper on Christina Kubisch and her electrical walks back in grad school. Reading through it again, I think the “finding narrative” section perhaps needs a revamp. That being said, I did a decent amount of research on both Kubisch’s work and the foundations of sound walks in general, so I thought it was worth posting. Enjoy!

Electrical Walks and the Living Narratives of Cities

Introduction

In her electrical walks, Christina Kubisch provides walkers with a pair of headphones and asks them to explore the city. The headphones are not normal headphones. These headphones plug into the stories of the city. They are custom made headphones that convert the electromagnetic fields given off by any electronic device into sounds. Each walker explores the city, making choices and discovering the hidden sounds of the city. Each electrical walk produces a personal mix of the city created by the walker, who plays both spectator and artist in the context of the walk. By participating in the project, each walker is exposed to and asked to express the stories of the city in whatever way they deem fit. What, if any, meaning is behind these electrical walks? What does the living, breathing narrative of the city sound like?

This paper is divided into several sections. Since these electrical walks are a deviation from the more traditional soundwalks, the first section takes a look at the basic purpose and theory behind them. The second part gives a history of how Kubisch’s work as well as how she developed her electrical walks and describes what the experience is like. The next section defines these electrical walks in the context of participatory art and explains how the walkers can manipulate the sounds and how and why this makes this participatory. Finally, the last section will put everything together and attempt to answer questions of narrative and meaning related to the electrical walks.

-

Beth B’s Stigmata and The Cinema of Transgression

Today, we’ll be taking a look at Beth B’s Stigmata. Before we can do that, we need to talk about a bit about Structuralism. The Structural film movement seemed to be a response to the seemingly complex experimental films that came shortly before it. Those working within the movement wanted to return to a simpler film form. The filmmakers considered to be part of the Cinema of Transgression were responding to the Structural movement. They found Structuralism to be boring and even elitist. According to Nick Zedd’s manifesto, they wanted film to be dangerous again.

In terms of imagery, the film is very simple. Most of the film features six persons, centered, at medium close-up. On top of that, there are some different shots used sparingly throughout the film: a bird flying in a building, a POV shot of someone looking out of a window, a horse pulling a carriage, older people sitting on a bench.

The film begins with the six interviewees talking about their horrible childhoods and the great pain they felt inside of them. They all begin talking about how they dealt with that pain, eventually leading to the fact that they were all drug addicts. As the film goes on they all talk about their experience with abusing drugs and then how they all eventually decided to get treatment. The use of the talking heads and the almost non-existence of an interviewer immediately reminded me of Errol Morris. I find it really interesting to just sit back and listen to people talk in this manner.

Looking at the film in formal terms, I was almost surprised to read afterward that Cinema of Transgression was a response to what people didn’t like about Structural film. I liked this film, but in terms of form, I wouldn’t exactly call it exciting or dangerous. In fact, a lot of Structural films probably contained more camera movement.

The main difference would be the content. In Structural film, the form tends to be (or is valued more than) the content. The strength of this film is the content. Based on the title, I actually thought the interviewees would all claim to have experienced stigmata. As it went on it, I thought it would be about suicide attempts. By the time I figured out it was about drug addiction, I was so interested in them and their stories, I wasn’t even thinking about what the film was about. It also fits into the Cinema of Transgression because the film is about drug addiction and as Peterson points out that Postmodernist films of this kind tend to seek out kinds of impurity.

While I liked the film I do have mixed feelings on the run time. Part of me feels like it was just a little too long and another part feels that that thirty-eight minutes wasn’t nearly enough time to learn about these people and their struggles. I mentioned how Errol Morris uses a similar kind of interview technique (I’m guessing Beth B. didn’t use an interrotron) and part of the reason his films are great because of the way he blends music, re-enactments, and graphics with the interviews. I don’t believe the simplicity hurts the film, but if this is supposed to be a kind of attack on Structuralism, I expected just a little more excitement.

-

Evangelion Reference in Once and Again

On this, the eve of Evangelion dropping on Netflix, I present to you the scene in Once and Again where the uber popular anime series is mentioned. This from from season 2, episode 7, “Learner’s Permit.” In this episode, Grace goes out with Pace’s annoying friend, Spencer, in hopes that Pace will become jealous and ask her on a date. The two do share a moment, and a kiss, brought on by the power of Evangelion discussion.

-

Looking Back At Picket Fences

A Critical Analysis of Picket Fences:

Season 1, Episode 18

“The Body Politic”

INTRODUCTION

After working on L.A. Law as a writer and story editor for five seasons, lawyer-turned-writer Dave E. Kelley wanted to focus on a show of his own. The show was an hour-long dramedy based around the family of the sheriff of the fictitious town of Rome, Wisconsin. CBS worked a deal out with Kelley and the first episode of Picket Fences aired on September 18, 1992. Combining high drama, low humor, controversial issues, and some of the most memorable plotlines and characters television has ever seen, Picket Fences ran for four seasons, winning fourteen Emmy awards and two Golden Globes. This paper serves as a critical analysis, defining and exploring how different aspects of Picket Fences worked together to create one of the best television shows of the last few decades.

THESIS AND LOGLINE

The thesis of the show can be found within the title. The white picket fence is a symbol associated with happy suburban living. It symbolizes the American Dream: a fulfilling job, a sizable stable income, and a nice house filled with a happy family. The basic theme of Picket Fences is that underneath all the guise of prosperity and happiness, life is weirder and a lot more complicated than people let on. It looks at where one person’s rights begin and another’s end, which is appropriate as fences are often used to mark boundaries. Ordinary people struggle with complicated ethical and moral issues every day and the answers are not always easy. David Lynch used the symbol of a picket fence ironically in his 1986 film Blue Velvet, which explored the dark underbelly of a suburban neighborhood. While the title of the show may be viewed as ironic, the show does not treat its content ironically. It creates real characters that are usually trying to do the right thing or to understand their own prejudices against others. The problem is that the “right thing” is not always clear.

The logline for the show is: an aging sheriff tries to keep the peace in a small town plagued by bizarre and violent crimes. As the sheriff, it is Jimmy’s job to keep the town under control and the focus of the show usually revolves around him and his family. While perhaps simplified, the logline does an adequate job of describing the basic premise of Picket Fences. The use of the word “bizarre” also prepares the audience for the use of unconventional plotlines.

-

The Catharsis of the Void in Anime Horror: Vampire Princess Miyu

The anime horror television series, Vampire Princess Miyu, turns 22 this year. It’s a weird anniversary to note, but appropriate for a series that didn’t get a 10th or 20th-year celebration. Despite being one of the better series to come out of Studio AIC in the ’90s, over two decades later, it seems to be largely forgotten in the US. What was Vampire Princess Miyu? Why did it disappear? Is it worth remembering?

Welcome to Miyu’s Dark Realm

Vampire Princess Miyu is a 26-episode television series that aired on TV Tokyo from 7 October 1997 to 31 March 1998. It was originally a manga series created by manga artist and director Narumi Kakinouchi and her husband, Toshiki Hirano. It ran for ten volumes between 1988 and 2002. Aside from the television series, it produced several spin-off series, as well as a four-episode Original Video Animation (OVA), in 1988.

Kakinouchi and Hirano have both worked in the anime and manga industry for decades in various positions. Kakinouchi is mainly known as a manga artist, with her most popular work being Vampire Princess Miyu. Hirano directed the Miyu OVA and TV series; he’s probably known best for directing Magic Knight Rayearth.

This article was written for PopMatters. Please read the full article here.

-

Shirley Clarke’s Bridges-Go-Round

When I think of Structural film my mind goes right to Paul Sharits’ T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G. This is probably due to the fact that T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G meets all of Sitney’s requirements to be considered structural. It was also the only film that I feel physically assaulted me so, that probably helps it stand out in my mind. Going forward into my perception of structural films, I think of slow, simple, often intentionally frustrating films where the form is more important than the content. I enjoyed Shirley Clarke’s Bridges-Go-Round, though it didn’t exactly fit my understanding of the definition of structural film. I’m going to analyze the film in terms of Sitney’s definition of structural film and then give a personal response to the work overall.

Sitney states that there are four characteristics inherent to structural film. The first characteristic is that the camera is fixed. The camera does not tilt, pan, or zoom: it stays static throughout. The second characteristic is that there is a strobe or flicker effect used. Looping, or repetition, is the third characteristic. Lastly, some type of retouching needs to be done to the film in post-production. While not listed directly by Sitney, it is usually the case that structural films value form over content.

-

Paradise PD Review

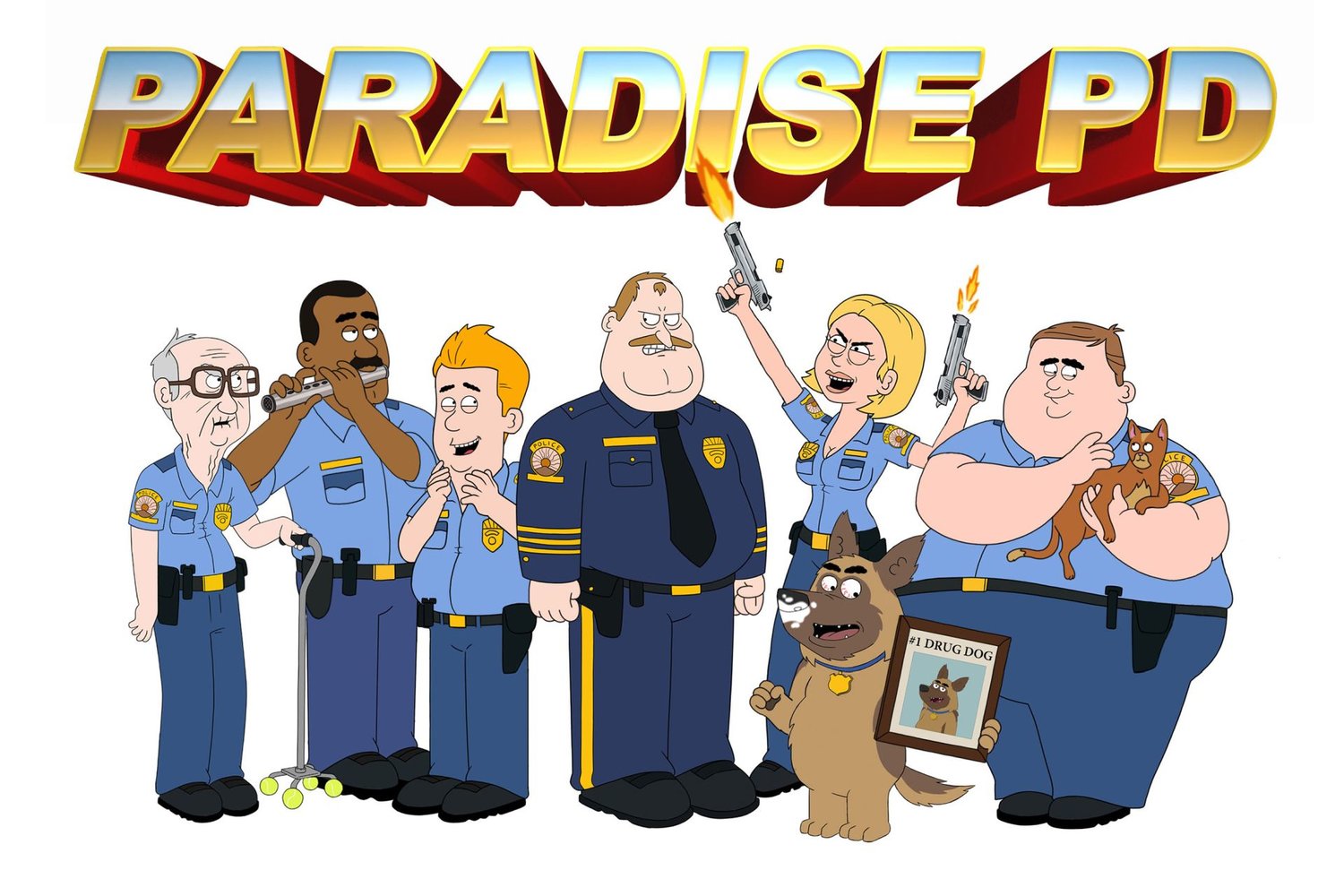

In the beginning, there was this show on Comedy Central called Brickleberry. I never really watched it. It got canceled. And I guess the creators just got a new show on Netflix called Paradise PD.

The series appropriately follows the misadventures of the police department in the titular city of Paradise. The characters that make up the police department are as deep as any paper plate. There’s black cop, woman cop, fat guy cop, old cop, drug-addicted dog cop, the chief, and his bumbling-but-well-meaning son

Each episode follows the Paradise PD as they solve a case or face a dilemma of some kind. While each episode is mostly independent, there are some ongoing serialized plot threads that come together, especially during the tenth and final episode of this season.

-

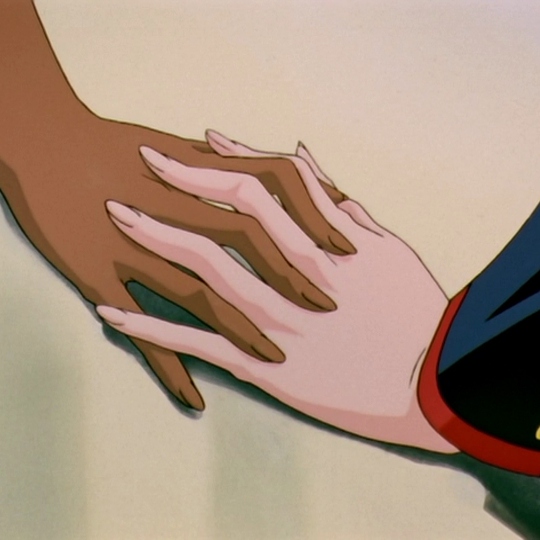

Is Revolutionary Girl Utena A White Savior Series?

Is Revolutionary Girl Utena A White Savior Series?

The first issue I have with reading Utena as a white savior title is that I’m not quite sure Utena is actually white. Caucasians tend to see anime characters as caucasian because to them, that’s the default race. To the Japanese, they’re Japanese. Also, all the characters in the show speak the Japanese language, have Japanese names, understand Japanese customs, etc…

While Anthy and Akio have a darker skin tone than the other characters in the show, I can’t think of a single instance where their skin color had any impact on any of the happenings in the story. Race is never even acknowledged. I’m sure an argument could be made for the other side, but I honestly think people are grasping at straws when they’re looking for commentary on race or racial relations in this series. This brings us to a white savior title in which the probably-not -white character saves the maybe-kinda-Indian character in a narrative where race has no real meaning. That doesn’t quite fit the bill, does it?